A Hybrid Approach to Best Practice for Japan

In today’s increasingly interconnected business environment, leadership drives performance—companies with strong global leaders are 2.3 times more likely to financially outperform competitors[1].

However while most senior executives agree that dedicated global leadership development efforts are vital, only 7% believe they are developing global leaders effectively. Nearly a third of US companies have reported that lack of leadership capacity prevented them from taking advantage of global business opportunities.

Japanese multinational companies likewise projected that globalization of management would be a top priority by 2015. Yet Japan still faces a shortage of leaders capable of competing and succeeding in the global marketplace.

To succeed globally, companies worldwide will need to find systematic ways to strengthen their leadership development approaches.

For Japan, this means rethinking which aspects of their business and management practice to globalize, and which traditional Japanese strengths to apply to a 21st century global economy.

What makes a global leader?

Business performance today is increasingly driven by rapid technological change, globalization, and social impact. Companies need to be more agile in order to remain globally competitive, which in turn requires not only strong leadership overall but also a particular focus the qualities that allow

Business performance today is increasingly driven by rapid technological change, globalization, and social impact. Companies need to be more agile in order to remain globally competitive, which in turn requires not only strong leadership overall but also a particular focus the qualities that allow

business leaders to be effective on the global stage.

Twenty-first century business leadership requires a reassessment of traditional “vertical”management styles built around leaders’ ability to inspire action, facilitate teambuilding, and exhibit strategic business acumen. Recent research consistently finds that while business and financial acumen remain important, social skills are what differentiate leaders in global environments. Global business leaders need to develop new “horizontal” management competencies organized around three key themes: context, complexity, and connectedness.

____________________________________________________________

Global business leaders need to develop new “horizontal” management competencies organized around three key themes: context, complexity, and connectedness.

_____________________________________________________________

Global Leadership Development in Practice

Senior executives across the board agree that global leaders need to be consciously and systematically cultivated in order for their businesses to grow. Yet the vast majority believes they are doing an inadequate job of it. Anecdotal studies of US companies suggest that 90% of resources spent on corporate training and development fail to deliver concrete results.[2]

Multinational companies are increasingly taking action by utilizing a range of methods, some of them time-tested and others more innovative. The common thread is that these methods are aimed at developing the intercultural competencies required for global success.

Corporate universities

The corporate university was first innovated by GE in 1919 and has since the 1960s become the norm among major US and European multinationals. Typically, the corporate university comprises a range of formal in-house programs designed around two primary functions: to disseminate firm-specific knowledge, and to propagate company culture. The model has evolved to the changing demands of global business, with the more successful programs moving beyond traditional classroom-based learning towards more experiential and networked practices. Still, many programs fail to build the social and

communication-based skillsets needed in global leaders.

Experiential learning

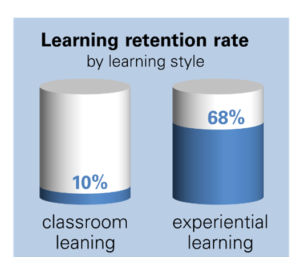

Adults retain over two-thirds of what is learned experientially, compared with only 10% of what is learned in a lecture or classroom setting. However, until recently most formal leadership development programs still relied on traditional classroom and e-learning training. What experiential training existed was often conducted informally through on-the-job experiences. Today’s highest-performing organizations are taking experiential learning seriously. Studies indicate that more than half have formalized experiential learning programs in their general training. Moreover, they were found to be four times more likely than low-performing peers to employ experiential learning in developing management-level leaders.

Adults retain over two-thirds of what is learned experientially, compared with only 10% of what is learned in a lecture or classroom setting. However, until recently most formal leadership development programs still relied on traditional classroom and e-learning training. What experiential training existed was often conducted informally through on-the-job experiences. Today’s highest-performing organizations are taking experiential learning seriously. Studies indicate that more than half have formalized experiential learning programs in their general training. Moreover, they were found to be four times more likely than low-performing peers to employ experiential learning in developing management-level leaders.

Mentoring

Mentorship has traditionally been used to enhance experiential training, filling in gaps where more formal leadership development programs has been absent. At their best, mentor programs provide a systematic way to global leaders. However, traditional top-down mentorship too often crowds out other forms of coaching-style learning relationships, especially peer learning. This is despite the fact that workers typically turn to peers before bosses to learn new skills, and that peer-to-peer learning builds emotional intelligence as well as cognitive skills, making it particularly well suited to the skillsets that global leaders need.

Global talent management systems

Most globally successful companies have implemented some form of network-wide global talent management system. This is critical for building and retaining a diverse internal talent pool. Best practices include globally standardized practices and KPIs that are aligned with company culture and strategic vision, but crucially leave room for local adaptation. Successful talent management systems are able to adapt to changing workforces, for example by offering flexible working arrangements to strategically attract top talent or by integrating social indicators such as cultural fit into KPIs and assessments.

Most globally successful companies have implemented some form of network-wide global talent management system. This is critical for building and retaining a diverse internal talent pool. Best practices include globally standardized practices and KPIs that are aligned with company culture and strategic vision, but crucially leave room for local adaptation. Successful talent management systems are able to adapt to changing workforces, for example by offering flexible working arrangements to strategically attract top talent or by integrating social indicators such as cultural fit into KPIs and assessments.

“Personal Learning Cloud”

Online courses, platforms, and learning tools have proliferated to address the shortcomings of traditional executive education in filling motivations gaps, skills gaps, and skills transfer gaps. Learning can easily and cost-effectively be personalized, adapted, and scaled, while organizations have access to increasingly sophisticated data in tracking and assessing ROI in leadership development. Leveraging these online platforms will become increasingly critical to competitive advantage as companies innovate low-cost, broadly accessible, scalable, and customizable alternatives or supplements to traditional leadership development and knowledge transfer.

While the practices described above can be found among the most successful global companies they by no means universally adopted. They are more deal benchmarks rather than standard practice. The time is ripe to invest in systematizing global leadership development in ways that can leapfrog inefficiencies in current practice.

Globalization of Japanese Business and Leadership Development

The traditional pillars of Japanese human resource management—lifetime employment, seniority-based leadership and advancement, and enterprise unions—evolved in the context of 20th century industrial development. These practices helped drive Japan’s postwar economic success, building a competitive economy known for high-quality manufactured goods and a strong domestic consumer market.

domestically are proving to be barriers to globalizaiton.

However the very practices that underlie the success

of Japanese companies

Globalization is an increasingly

urgent necessity for Japan. The population is declining, and domestic consumption has been stagnant for decades while foreign competition and FDI have grown rapidly. Companies have no choice by to look outside Japan for growth opportunities.

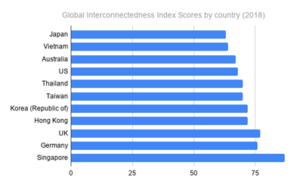

Despite this push to globalize, Japan ranks low in global interconnectedness compared with nearly all its regional trading partners and economic peers. Risk averse and conservative business practices, insularity, and a persistent lack of diversity at all levels of employment remain barriers to Japan’s global competitiveness.

Recognizing the need for change, Japanese companies have started taking steps to strengthening their global leadership capacities. However because these efforts are not systematic, companies still struggle to overcome a number of challenges specific to Japan.

Japanese Global Leadership Development Practices

Traditional leadership development in Japan has involved little formal training. It relies instead on informal on-the-job experiences, most often through job rotations aimed at comprehensive exposure to operations company-wide.

Such standard domestic practices are typically applied to training global leaders as well as domestic managers, with uneven success. Not all domestic ways are transferrable directly to a global business environment. But neither should they be abandoned—there is too much good in them. Such practices include:

On-the-job training

On-the-job training, most often relying on job rotations, is used ubiquitously to familiarize employees with the comprehensive company knowledge desired in upcoming senior leadership. However this type of training for future leaders is practiced unevenly among global management. Because the goals of such training are poorly articulated and delinked from clear career development pathways, Japanese firms struggle to attract and retain promising global talent. Consequently, global leadership rotation practices have created cleavages and communication barriers between local management and a rotating cadre of temporary executive expatriates.

Team-based experiential training

Team-based organizational structures foster a form of on-the-job experiential training particularly attuned to building the consensus-based leadership skills traditionally valued in Japan. For example, Okawara Power Equipment (OPE) uses a Junior Board structure to build leadership and management skills among promising mid-level employees. The Junior Board has helped to identify key barriers to the company’s global expansion as well as mechanisms for reform. The Board launched a training system to guide new employees’ exposure to other departments, accelerating and systematizing the job rotation process. Such team-based experiential learning is becoming increasingly important on the global stage.

Internal human resource management

Japanese firms are beginning to orient their human resource management systems towards developing global talent into future leaders, but efforts remain sporadic. SY Systems, a Nagoya-based software development and consulting firm, has utilized

its HR system to identify and cycle overseas employees to Japan for a three-year training program. It also calibrates pay scales for its Japanese employees according to foreign language scores on the JLPT. Okawara Power Equipment (OPE), having identified a set of more active management skills desired in global leaders, has introduced human resource evaluations that capture employee motivation and whether they have achieved the desired behavioral qualities. Such efforts are steps in the right direction towards systematizing global leadership development. However they will remain limited in impact if the initiatives remain sporadic and delinked from company-wide career development systems.

Japanese businesses stand to benefit enormously from more concerted efforts to systematize global leadership development. An ideal system would enhance current Japanese best practice with selected global standards as suits the needs of their industries and regions of operation.

6 ways forward for Japanese global leadership development

Japanese firms are losing out two-fold In today’s globalized talent market. First, their management and leadership development structures not only fail to attract, but often work to actively exclude top global talent. Second, Japan is failing to train its domestic workforce with the skills and core competencies needed to compete as leaders in today’s global marketplace.

To address these challenges, it is not necessary that Japanese companies abandon their current best practices. A more productive path to success would be to enhance current strengths by adopting a hybrid approach that combines Japanese leadership development practices with context-specific best practices that have proven successful globally.

We have identified six areas where a hybrid Japan-global leadership development system can be implemented.

- Get diversity right

Linguistic and cultural diversification is a crucial first step towards building a competent and consistently been shown to financially outperform their peers.

In the Japanese context, this means first of all a focus on women throughout all levels of management and senior leadership. With respect to non-Japanese talent, diversification requires a special focus on career development for local hires that goes beyond local subsidiary management. Eliminating the “rice paper ceiling” barring advancement of non-Japanese leaders is a necessary step. So is facilitating increased lateral mobility of global talent among subsidiaries as well as between subsidiaries and Japanese.

- Formalize leadership development

Global leadership development efforts worldwide would benefit from more structure and systematization. In Japan, this means a concerted focus on articulating clear job descriptions and career development pathways as well as formalizing a standard program of leadership development across the company, with robust metrics and KPIs that allow for monitoring and evaluation.

Traditional strengths of Japanese HR practice best suited to the current postindustrial global economy—consensus-based decision-making, culturally-rooted experiential learning practices, and kaizen, to name a few—should be supplemented with new and emerging global best practices.

Japanese strengths to draw on include broad generalized company knowledge, rotational flexibility, and strong company culture while global best practices include strong globalized career development and clearly articulated individual responsibilities linked to tangible company strategies.

- Create a worldwide “one-company” culture

Japanese companies are lauded for their strong corporate cultures, but in practice, these cultures are rarely communicated effectively to non-Japanese staff. Company culture in Japan tends to be disseminated in the form of values through various informal pathways. They often lack the clarity of the strategic corporate branding programs that inform company cultures elsewhere.

By starting with a formally articulated and professionally communicated brand, Japanese companies are in a stronger position to apply their traditional methods of inculcating values and culture to non-Japanese future leaders.

- Improve lateral mobility

Most Japanese multinational companies operate through a hub-and-spokes model with headquarters communicating directly with each subsidiary separately. These human resource siloes impede the increasingly networked dynamics of successful global business.

Moving talent across national boundaries can help spread essential knowledge and best practice throughout the network.

Cross-border mobility is also an invaluable learning tool for global leaders, creating a depth of intercultural knowledge and experience not possible with two-way exchange between Japan and individual subsidiaries.

At the same time, mobility multiplies the career advancement pathways for global talent, resulting in better job satisfaction, superior performance and enhanced retention.

- Boost Peer learning

Peer learning has long been an informal way for Japanese business to tr ansfer skills via on- the-job learning and informal mentoring. More recently successful companies are systematizing peer learning, building it into a more strategic and sustainable learning strategy.

ansfer skills via on- the-job learning and informal mentoring. More recently successful companies are systematizing peer learning, building it into a more strategic and sustainable learning strategy.

Learners and skill owners are carefully assessed and matched and before learning sessions begin skill owner are coached in the most effective teaching methods.

Taking advantage of the recent proliferation in cloud-based platforms, learning sessions are captured on video for later use by new learners and learning sustainment by the original learners. Peer learning assets can be organized into searchable libraries that are easily accessible from multiple devices, creating an accessible and scalable internal leadership development resource for globalizing companies.

A mature Peer Learning system solves one of the persistent issues Japanese leaders serving overseas face; ensuring that high-level Japanese skills are transferred effectively to local staff, reducing dependence on high-cost Japanese expat experts.

- Implement a global HR system

The above five directions for global leadership development cannot be effectively implemented without a globally standardized human resource management system

Such a system will ensure that company culture is strategically and systematically communicated across regional and functional differences, and align KPIs and pay scales to facilitate lateral mobility and maximize the strengths and leadership potential of its internal talent pool.

Most importantly, it is a standardized system that allows for global integration, while also allowing for adequate adjustments to ensure not just compliance with local standards but also the productive leveraging of local resources and competitive advantage.

Japanese companies have developed a unique set of assets for developing business leaders, among them strong company cultures, a team-based approach to learning and development and a focus on comprehensive experiential training. But if they are to develop truly effective global leaders within Japan while also attracting top global talent, companies will need to make improvements in two key areas:

systematization, and intercultural communication.

By adding these competencies in a way that strengthens rather than replaces existing skillsets, Japanese companies can create a powerful hybrid leadership development capability. A new cadre of global leaders can become one of Japan’s decisive competitive advantages into the 21st century

_______________________________

[1] Deloitte Consulting GmbH (2017). Building Future Ready Leaders.

[2] Moldoveanu, M. & Narayandas, D. (2019). Educating the Next Generation of Leaders: The Future of Leadership Development. Harvard Business Review.

For more information and resources for globalizing Japanese business, visit

https://j-globalgroup.com/